News across the world, and about the book...

On this page, I regularly post developments across the world that are of relevance to energy storage, distrubution and portability. I also report on the attention that The Decarbonization Delusion is receiving.

Historic journey re-enacted with renewable methanol fuel: the OBRIST story

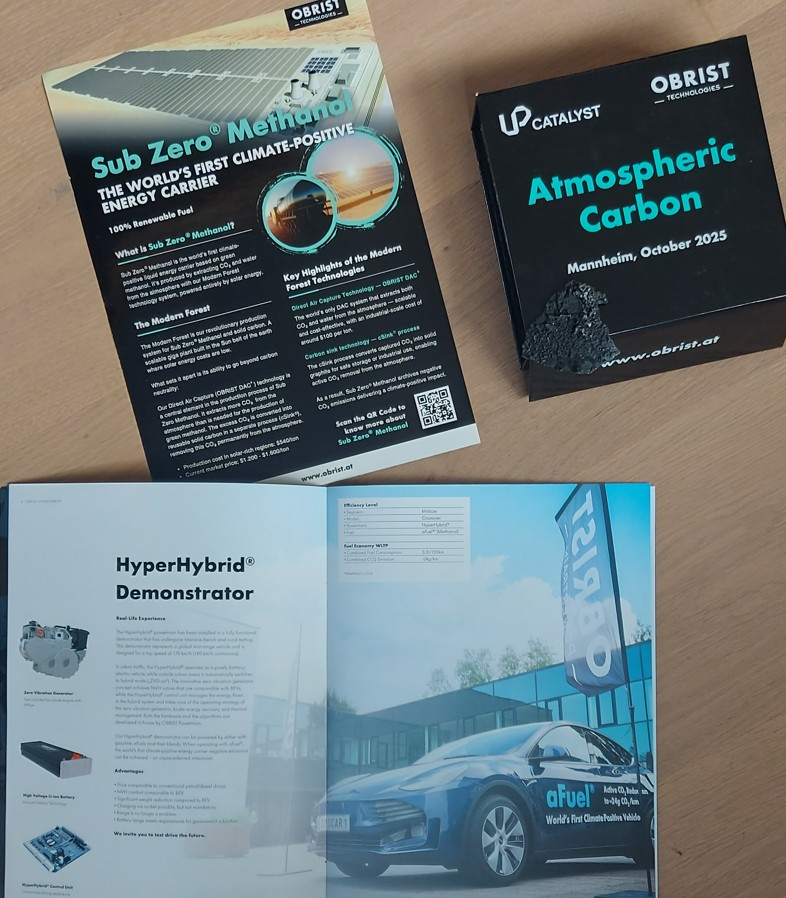

In 1888, Bertha Benz, Carl Benz’s wife, was the first to drive any distance in a car with an internal combustion engine: from the industry town of Mannheim to the small town of Wiesloch — where she filled up again at an now famous pharmacy — and back again. The re-enactment of this journey, in October 2025, this time producing no net CO2 emissions, caused a sensation too.

The vehicle, above, with company director Frank Obrist standing next to it, is a highly-modified Tesla, from which the very heavy and resource-intensive battery has been removed. This battery has been replaced with a very small one. It acts merely as an energy buffer between a methanol-powered internal combustion engine(ICE)/e-generator and an electric motor driving the wheels (a so-called “serial hybrid” — the invention of Frank OBRIST and the highly innovative OBRIST Group from Austria. It’s a hybrid, where the methanol-driven ICE mostly runs in a relatively high r.p.m. range, generating maximum efficiency (around 50%). This, the greatly reduced battery mass in this car, combined with CO2-free methanol fuel actually makes this car produce much less CO2 throughought its entire life cycle than the fully-electric Tesla! And it also does less environmental harm, because less mineral mining is required for the much smaller battery! The methanol tanked here is in fact so-called a-methanol or Sub-Zero-methanol:

because it is produced with CO2 from the atmosphere in a special reactor that reacts the CO2 with hydrogen (H2):

The other branch of the CO2 extraction chain actually creates solid highly-pure carbon, which can be used for a variety of purposes, e.g. carbon fiber, graphite for battery anodes, metallurgy, filtration technology etc. etc. even adding to nutritionally-depleted farmland to restore fertility and soil structure. Remaining solid in most of these applications for many years, it very useful draws carbon out of the atmosphere, helping to reduce the ppm CO2 there, and hence reduce global warming. Here’s a piece of pure carbon, direct from the reactor!

So, fully tanked, three of the “HyperHybrid” cars set off from Mannheim, arrived in Wiesloch, took some more CO2-free methanol onboard, and returned to Mannheim.

The final analysis, done by a registered notary, indeed showed that the drive, in combination with the manufacturing process that also produced solid carbon, was, indeed CO2-negative! The whole process actually left the atmosphere with less CO2 than at the beginning!

The whole event, which started with a number of very informative talks from the OBRIST team and their associated business partners was very well covered by the media. It highlighted the exciting potential for building massive renewable electricity facilities, particularly solar (photovoltaic) panel arrays in deserts, and making methanol directly on site. This would then be exported to consumer countries for a variety of sectors, from road transport, through cement production, to gas-fired power stations, which can very easily be adapted to run on methanol instead of natural gas. Remember, THIS methanol does not, in net effect, increase atmosphereic ppm of CO2! Massive opportunities exist here to start collaborations and alliances with countries with large quantities of CO2-free energy: jobs, economic development, future-driven technology. It could be a perfect match! We desperately need environmentally-sympathetic ways of storing the massive excesses of energy that we are able to harvest, otherwise this wastage turns into environmental impacts that we should be avoiding.

Finally, at much more local scale, most countries have massive potential to capitalize on CO2 emissions that are otherwise left to escape into the atmosphere. The event described above was hosted by the Mannheim waste water treatment plant (Kläranlage), where the methanol and carbon production reactors for this event are situated. It’s a collaboration between two industrial sectors: the water purification plant uses microbes to ferment, and hence purify water. These give off large amounts of CO2 (and methane). What better than to harness that CO2 for something useful, and that’s exactly what OBRIST, in collaboration with the Klärwerk Mannheim has done! Let’s hope that many more collasborative and environmentally-conscious initiatives of this sort take of and rapidly expand what I conclude is an extremely promising industrial and environmental concept! INVESTORS INVITED!

Some media coverage of the event:

https://www.presseportal.de/pm/172771/6130643

https://www.swr.de/swraktuell-radio/erste-klimapositive-autofahrt-100.html

https://www.euroguss.de/de-de/euroguss-365/2025/news/worlds-first-climate-positive-car

https://www.rnf.de/mediathek/video/mannheim-auf-dem-weg-zur-klimapositiven-spritrevolution/

First gas station in the European Union to offer 95% CO2-free gasoline

Near Bremen, Germany, the first “eBenzin” gas station opened this June. The e-gasoline (an e-fuel) that one can buy there is made from CO2 extracted from the atmosphere or industrial flue gases plus hydrogen made by splitting water with electricity (electrolysis). These are then — to put it simply — reacted via chemical catalytic processes to make the synthetic fuel. https://www.cac-chem.de/news-detail/europapremiere-an-der-zapfsaeule

Do metals in catalytic converters represent comparable environmental impacts to constituents in EV batteries? Short answer: “no”, far from it. <Download pdf>

I simply must write this little analysis, because I am constantly being reminded by EV advocates that catalytic converters produce massive environmental damage in their production, because of the mining and purifying of the rare metals they contain: rhodium, palladium and platinum. Per gram, these metals do have a large energy and CO2 emissions impact; however extremely small amounts are used in catalytic converters. So I compared a typical catalytic converter with a typical lithium NMC battery, still the type that auto manufacturers strongly prefer for performance, longevity and driving range. It’s extremely difficult to quantify the environmental impacts, because the three rare metals mentioned are invariably by-products from other metal-ore-mining activities. However, the energy required for their mining and refining can quite reliably be calculated, and many people have done that; similarly for the components of Li-NMC batteris. Here’s the result that I obtain by using these figures:

An average EV Li-NMC battery requires more than 7.4 times as much energy for the production of its electrically-vital components as an average catalytic converter for the production of its chemically-vital components.

The details are below, for those who wish to inspect them. Some might say, “but battery technology is advancing, and we are producing different kinds of battery…” well, true, but not fast enough for the environment! Moreover, the technology of catalytic converters is also not standing still. Those who keep up to date with developments will know that much more common metals are already in use, and being developed for some catalytic converters. Even the European Commission has been supporting these developments from as early as 2016 (https://cordis.europa.eu/project/id/280890/reporting/fr). This whole area of environmental impacts of technology is a moving picture: we must be aware of that, and support technology diversity.

Here are the details:

Values from, among other sources: https://elements.visualcapitalist.com/the-key-minerals-in-an-ev-battery/ for kg, and widely available sources, averaged, for PED (primary energy demand of manufacture from minine through to finished metal).

Masses of EV battery components, followed by energy of manufacture from natural resources (mining):

-

Graphite: 52 kg @ PED 31.3 MWh/tonne = 112,680 MJ/tonne = 113 MJ/kg => 5,876 MJ

-

Aluminium: 35 kg @ PED 17 MWh/ tonne = 61,200 MJ/tonne = 61 MJ/kg => 2,135 MJ

-

Nickel: 29 kg @ PED 80 MWh/tonne = 288,000 MJ/tonne = 288 MJ/kg => 8,352 MJ

-

Copper: 20 kg @ PED 8 MWh/ tonne = 28,800 MJ/tonne = 29 MJ/kg => 580 MJ

-

Manganese: 10 kg @ PED = 16.5 MJ/kg, equating to 16,500 MJ/tonne (MDPI ref. https://www.mdpi.com/2313-0105/8/8/76?utm_source=chatgpt.com) = 16.5 MJ/kg => 165 MJ

-

Cobalt: 8 kg @ PED 28 MWh/tonne = 100,800 MJ/tonne = 101 MJ/kg => 808 MJ

-

Lithium: 6 kg – equating to around 57 kg of lithium hydroxide monohydrate @ PED (in form of lithium hydroxide monohydrate), unweighted average between brine and rock-ore production routes 73 MWh/tonne = 262,800 MJ/tonne = 263 MJ/kg => 14,999 MJ (i.e. 57 x 263)

______________________________________________________________________

Total: 32,915 MJ of energy (result 1)

___________________________________________________

Figures for a typical catalytic converter:

Calculation of total PED PRIMARY PRODUCTION for a typical catalytic converter (masses in grams of metal), followed by energy requirement for extraction (mining) and refining:

- Rhodium: 1.5 g => 1.5 x 437 (mean from table 2) = 656 MJ

- Platinum: 5.0 g => 5.0 x 454 (mean from table 2) = 2,270 MJ

- Palladium: 4.5 g => 4.5 x 332 (mean from table 2) = 1,494 MJ

___________________________________________________

Total: 4,420 MJ (result 2)

___________________________________________________

Result 1 divided by result 2 = 7.44 i.e. the battery requires, just for the components noted, 7.44 times as much energy in its manufacture. Note, not included in this calculation is the complex process of manufacturing hundreds of individual cells and building them together into the final battery pack; neither is the process of casting the ceramic carrier for the catalytic converter.

Note: the energy needed to manufacture something (the embodied energy) is closely related to the environmental impact. It’s not a 1:1 relationship, but in the realms of metal sourcing and refining, comparisons across different metals are pretty close, because much thermal energy is required, which at present comes almost entirely from the burning of fossil fuels. Furthermore, much water is used, which directly equates to fresh water depletion in the areas concerned. Also, in mining of any kind, a great deal of collateral damage is done by the release of other minerals, and contamination of land via watery sludges that arise during the mechanical crushing and processing.

What about recycling?

Note, the well-established processes of recycling for rhodium, palladium and platinum from catalytic converters produces, on average across the three metals, rates of recuperation of 90% or more. Such high rates are extremely difficult, if not currently impossible, to obtain for the components of lithium-ion batteries. Particularly for lithium, the rate of practical recuperation is no higher than 50%, and that at great energetic cost. Here we see another interesting factor, because if you look at tables 2 and 3 below, you will see that the energy needed to recuperate the metals from catalytic converters is only 2% of the energy needed to mine them from primary sources (ores). However, in the case of lithium, the energy needed to extract it from spent batteries seems to be greater than the energy needed to mine and purify it from primary sources (brines or ores). This leads to the widely-acknowledged feature of battery manufacture: it’s cheaper to make batteries from freshly mined lithium than from recycled lithium. This economic quandary is a serious factor determining the success of battery recycling factories, which are currently struggling. Note, the combined manufacturing and recycling plant by Northvolt in Europe filed for bankruptcy earlier in 2025. Lithium is, despite what many think, a highly problematic mineral in battery manufacture. It requires an enormous amount of energy and water to extract and refine/convert into battery-usable form compared with the other battery compoentns. That said, nickel as a component of batteries is on the rise, leading to large-scale deforestation in Indonesia because of open-cast mining.

Data sources:

Tables 2 and 3 from https://ipa-news.de/assets/pdfs/2022-06-21-new-environmental-profile-of-pgms-ipa.pdf:

____________________________________________

At the Max-Planck Institute for Terrestrial Microbiology in Margurg, Germany, a research group under the leadership of Professor Tobias Erb is working towards artificial photosynthesis…

Surely natural photosynthesis is good enough, right? Not for human challenges, because the key enzyme that incorporates CO2 into biological molecules, i.e. “fixes” CO2, is too slow!

The enzyme RUBISCO takes CO2 from the atmosphere, and a form of hydrogen from the splitting of water with sunlight, and generates glucose, which is the building block for most other biological molecules in plants. RUBISCO “fixes” around 8 CO2 molecules per second; but Tobias Erb’s group has engineered a version that is ten times as fast! They are also working on building the chains of other enzymes that work after RUBISCO in lant metabolism, producing countless molecules that are extremely useful to us humans: from materials, through fuels, to medicines. Could we soon have artificial metabolic pathways that turn sunlight and CO2 into economically valuable materials other than wood? Quite possibly! One can’t help but be enthsiastic when watching Prof. Erb talk about his research here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CPFscyYRS10

A recent paper from him and his group looks into accelerating another key enzyme in the photosynthesis chain:

____________________________________________

Can we really create the necessary electricity storage buffer for the world with batteries? Here’s something that will surely make you think again…

The energy storage problem rears its imploring head in many circumstances, and here’s another one. A very recent report presents scenarios for storing electricity in batteries vor various amounts of time to even out some of the natural variations in regenerative electricity generation. Even for a relatively modest storage period of 28 days, the batteries that we would need globally — at current practicable battery technology and chemistry — would massively exceed the amounts of many of the key respective metals that are in Earth’s reserves — yes, even Lithium. Interestingly, even graphite (for battery anodes) would, in this scenario, only be satisfied to 10% by Earth’s reserves… Surely this speaks for the need for technology diversity in energy storage solutions…

From 2024 report available at: https://tupa.gtk.fi/julkaisu/bulletin/bt_416.pdf

____________________________________________

How much water would a country need, in order to make its primary energy in the form of hydrogen?

I just picked this one up via Linkedin, so I thought I’d have a go at it with the example of Spain given in the question:

Bottom line – well, actually the top line 🙂 with the assumptions made below, the amount of water needed in Spain for the necessary hydrogen per year would be 2.6% of current agricultural use of water in Spain per year. Note, this is based SOLELY on the assumptions and information below: it is not necessarily realistic, but gives some kind of idea…

Here’s a back-of-an-envelope calculation that I’ve just done, assuming the following:

1. We very crudely equate current primary energy consumption in Spain directly 1:1 with equivalent energy from hydrogen. This definitely isn’t 100% accurate, because, for example, hydrogen-fired steel-making uses less MWh per tonne of steel than coal-fired steel making. However, it gives us a reference point from which to refine the calculation.

2. Current annual primary energy consumption in Spain is around 1,600 Terawatts per year (see https://ourworldindata.org/energy/country/spain).

3. The electrolysis reaction is H2O -> H2 plus 0.5 O2

4. Molar masses (molecular „weights“) are H2O = 18 g/mol ; H2 = 2 g/mol which means, in terms of mass (weight), we need nine tonnes of water to make one tonne of hydrogen gas.

5. Hydrogen has a gravimetric energy density of 131 MJ/kg (averaged between HHV and LHV, because we don’t know whether we can recuperate the energy of water vapour formation); this is equal to 36 kWh/kg hydrogen gas.

The calculation:

1,600 TWh per year is 1.6 x 10EXP12 kWh per year

Divided by 36 kWh/kg hydrogen gas energy content => 4.4 x10EXP10 kg hydrogen

This equals 44 million tonnes of necessary hydrogen gas.

To make that via electrolysis, the theoretical minimum mass of water is 9 x 44 million tonnes, which = 400 million tonnes of necessary water.

How much are 400 million tonnes of water? – i.e. 400 million cubic meters.

From Statista, I get a value of 15,500 million cubic meters of water used currently in agriculture in Spain per year (see https://www.statista.com/statistics/1218844/irrigation-water-used-agricultural-sector-spain/) . So, 40 divided by 15,500 gives us a relation to current agricultural usage of water, and it equals 2.6%.

Bottom line: with the assumptions made above, the amount of water needed in Spain for the necessary hydrogen per year would be 2.6% of current agricultural use of water in Spain per year.

____________________________________________

On the impacts of mineral and ore mining…

2024, January: United Nations predicts serious environmental and social impacts of raw material mining up to 2060…

And see also report in Sustainability & Environment Network 2024.

Vortrag beim Lions Club Palatina, Heidelberg, am 08.09.2025 “Alles Akku, oder geht es vielleicht doch anders? Was wir von der Biologie lernen können und müssen…” <Präsentation hier herunterladen>

Visit to OBRIST, developer of carbon capture, a-fuel and carbon-negative technology, Lindau, Bavaria, Germany, on 11th December 2024

________________________________________________

Invited talk for the Max-Planck-Gesellschaft, at the MPI for Biological Intelligence, Martinsried, Bavaria, Germany, on 10th December 2024

________________________________________________

Invited talk for the Green Party (Bündnis 90 die Grünen) in the constituency Bad Tölz-Wolfratshausen, Bavaria, Germany, on 9th December 2024

English: Energy carriers of the future – what 3,5 billion years of biology can teach us

________________________________________________

Invited talk at the DAI (Deutsch-Amerikanisches Institut) Heidelberg, Baden-Württemberg, Germany on 12th November 2024

English: Energy carriers of the future – what 3,5 billion years of biology can teach us

Watch the  video of the talk here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=khb-aqFRUC4

video of the talk here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=khb-aqFRUC4

________________________________________________

Invited talk at the Lions Club in Lampertheim, Hessen, Germany on 17th September 2024

________________________________________________

Interview with India Bioscience in their series “Carbon Chronicles”:

________________________________________________

Invited talk at Colchester Royal Grammar School, in memory of Dr. Neil Cook, Chemistry Department CRGS

Download the presentation here.

________________________________________________

Book review on Chemistry Views news platform

________________________________________________

Book review in the scientific journal BioEssays

________________________________________________

Audio podcast: Andrew Moore interviewed by Adam Dixon, Adam Smith Chair of Sustainable Capitalism, Heriot-Watt University, Edinburgh. Series: New Enlightenment Channel

Video clip from the Panmure House interview with Prof. Adam Dixon.

________________________________________________

Q&A with renowned American journalist Deborah Kalb.

andrewmoorescientist.com Analyses and comparisons in energy and material economies Email